As in, The Great San Francisco Earthquake And Fire Of 1906.

Even if I hadn't been sold already, that would've done it.

With no release date pinned on the film at the time (though it's since been slated for sometime in 2009), I figured I would check out the book on which the movie is to be based, James Dalessandro's 1906. It was a quick read - I was able to get through the whole thing on one cross-country flight. And, well. If anyone can fix it, I trust Brad Bird can.

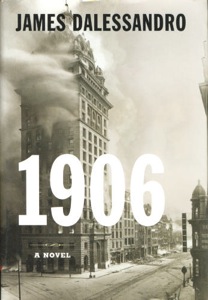

With no release date pinned on the film at the time (though it's since been slated for sometime in 2009), I figured I would check out the book on which the movie is to be based, James Dalessandro's 1906. It was a quick read - I was able to get through the whole thing on one cross-country flight. And, well. If anyone can fix it, I trust Brad Bird can.The novel suffers from some problems that are unrelated to the geology of the characters' situation. For one, the main character/narrator is a definite Mary Sue: she knows everyone who's anyone in San Francisco, is involved investigating the mayor (even though she's only media), gets to be Caruso's personal tour guide, owns Jack London's old typewriter, and so on, all at the age of 23. Her cop/engineer/geologist-with-a-degree-from-Stanford boyfriend isn't really any better. There are also some problems with the first person perspective, since there are scenes described in vivid detail that there's no way the protagonist would have seen (I'm talking, scene on a train coming from Kansas, let alone scene in the bad guys' secret lair). The entire story is laced with very heavy-handed foreshadowing, to the point where I was thinking, "Alright already, just get to the stinkin' earthquake!" Sure, when you pick up a book or go to see a movie called 1906 with a picture of the burning Call Building as the cover/promotional artwork, you know the earthquake is going to be a major plot point, but I think there are ways such a story could be written so that the reader/viewer, when immersed in the world being presented, would still not see it coming at the precise time that it does. The unexpectedness of earthquakes is a large part of the terror in them, and Dalessandro completely does away with that aspect. Furthermore, none of the main characters behave like normal human beings when the earthquake finally does strike. It comes at a point where there is already conflict going on, and when the shaking ends, the conflict picks up exactly where it left off, as if nothing had happened. One would think that at least a couple of people in the situation would have been utterly freaked out enough by the city shaking down around them to forget what they'd been doing before, or at least lose their place, but nobody in the scene seems to even bat an eye. Maybe they read all the foreshadowing from earlier in the book.

But for these faults (har har), 1906 has a problem that makes it quite singular among disaster movies - it has too much science. You heard right. Dalessandro clearly researched the cultural climate of turn of the 20th century San Francisco - his setting is detailed and colorful and lines up with all the history books I've read about this event so far. And he clearly did some research on the science of earthquakes - there's even a scene where two picnickers on San Andreas Lake notices an alarming rate of preseismic slip along the fault. The problem is that Dalessandro didn't cross reference the two - that is, he didn't check to see how much of that science was known in 1906. Thus, you get characters who are part of the general nonscientific public talking openly about the San Andreas Fault by name, even though it wasn't named until Andrew Lawson's 1908 report on the 1906 event. And the scientifically-inclined characters describe the fault as a boundary between the Pacific and North American plates, a good sixty years before the theory of plate tectonics was presented. Not to mention that scene with the picnic at the fault - the reason the picnic is there is one of the people on it is a seismologist who is deliberately measuring slip on the fault, monitoring it closely due to its threat to the city in the days before the quake. There's nothing scientifically incorrect here. It's just all displaced in time by a matter of years or decades - a huge oversight indeed.

The character stuff, the reactions, and the foreshadowing are all things that I'm sure Brad Bird can fix, since he's apparently in the process of rewriting an earlier version of the script. His other movies are much more subtle in their foreshadowing, and the characters are all more realistic, multifaceted, flawed people (or robots, or rats). I just really hope it occurs to the movie team to check their science and update the script - or perhaps backdate it, as the case may be.

I still plan on seeing 1906 when it comes out. I'm sure it'll look awesome, since Pixar is, it has been recently announced, involved. The murder mystery/tale of scandal of the book is still intriguing, even with the all-too-perfect characters and all-too-obvious earthquake. If worse comes to worse, 1906 will be next in a long line of disaster movies that are so bad that they're funny, but I doubt that, since it is a Brad Bird movie. I'm really hoping I'll be pleasantly surprised, and will be able to enjoy the film in earnest, without having to snark at anachronism.

1906 on IMDB

You know, it would be fun if a bunch of geobloggers went to see this together. Yeah.